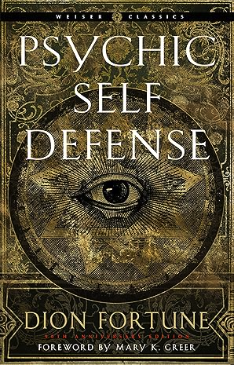

When I first picked up Dion Fortune’s Psychic Self-Defense, I half-expected a self-help manual, judging from the title. What I actually found was something closer to a casebook in “occult pathology” written for working practitioners in the early twentieth-century magical revival.

Fortune wrote Psychic Self-Defense around 1930, drawing heavily on her own experience of what she believed was a prolonged psychic attack that left her physically and mentally shattered for years. By then she was already an established British occultist: born Violet Mary Firth in 1890, trained in psychology at the University of London, working in a psychotherapy clinic, and deeply entangled with the Golden Dawn tradition before founding her own group, the Fraternity of the Inner Light (later the Society of the Inner Light).

The resulting book sits at a strange intersection: part memoir, part clinical notebook, part theological argument. It’s often shelved today under “parapsychology” or “psychic development” and marketed with subtitles like The Classic Instruction Manual for Protecting Yourself Against Paranormal Attack, but that packaging can be misleading. Fortune’s own emphasis (and the way the book is structured) makes much more sense if you think of it as a resource for occult workers and spiritual directors trying to discern whether a distressed person is dealing with mental illness, psychic assault, or some messy combination of the two.

Interestingly, later editions even lean into that diagnostic tone by using subtitles such as A Study in Occult Pathology and Criminality. I haven’t found any evidence that the core title was ever anything other than Psychic Self-Defence (spelled with the British “c”) in the original Rider & Co. edition, which appeared around 1930. What has shifted over time is the marketing language wrapped around it, with publishers emphasizing “instruction manual” and “self-defense” to appeal to contemporary readers looking for personal protection techniques.

The World As It Was When Dion Fortune Wrote

To understand the book, it helps to situate it inside the spiritual currents of her time.

Fortune stood at a crossroads where several streams met:

- Victorian and Edwardian spiritualism: Séances, mediumship, and communication with the dead were still part of the cultural memory, even as skepticism grew.

- Christian Science and New Thought: Movements that emphasized mind over matter, “mental science,” and healing through prayer or focused thought. Fortune spends several pages dissecting the darker possibilities of these methods, including what Mary Baker Eddy called “malicious animal magnetism.”

- Theosophy and the occult revival: The Golden Dawn, Theosophical Society, and related orders were experimenting with ceremonial magic, astral travel, and complex hierarchies of inner-plane beings. Fortune was very much inside this ecosystem, eventually founding her own society devoted to structured magical training.

Psychic Self-Defense is her attempt to talk plainly about what can go wrong in that environment: what happens when people discover the “powers of the human mind” and use them to manipulate others, consciously or unconsciously.

She writes as someone who has seen the overlap between psychotherapy and the occult up close, and she’s explicit about that. In the preface, she notes that her interest in psychology, and then in occultism as “the real key to psychology”, was forced on her by her own experience of psychic attack. That dual background shapes the whole book.

Not a Self-help Manual

If you come to Psychic Self-Defense expecting a modern “how to protect your energy” workbook, you may be surprised by how little of the text is devoted to techniques and how much to case studies and classification.

The structure tells the story:

- Part I – Types of Psychic Attack

- Part II – Differential Diagnosis

- Part III – The Diagnosis of a Psychic Attack

- Part IV – Methods of Defence Against Psychic Attack

The emphasis is on diagnosis and discernment, not on handing the reader a quick ritual and sending them on their way. In fact, a goodly part of the discussion centers on determining if a person is suffering solely from a mental health crisis, as opposed to a spiritual or psychic attack.

Fortune is very aware that many symptoms of alleged psychic attack look suspiciously like mental illness, trauma, or manipulation that could be explained without invoking spirits at all. Hence chapters like:

- “Distinction Between Objective Psychic Attack and Subjective Psychic Disturbance”

- “The Psychic Element in Mental Disturbance”

She’s trying, in her own early-20th-century way, to build a diagnostic grid: when is this an etheric issue, when is it psychological, and when is it both? And how do you help people who are suffering without either dismissing spiritual dimensions outright or blaming everything on demons and curses?

The book is firmly aimed at practitioners (occultists, spiritual healers, clergy, energy workers, etc.) who are already working with others, and not at a general audience. It’s quite possible to read it as a reminder that anyone in that role should stay in conversation with conventional medicine and psychology rather than jumping to a purely esoteric explanation.

Her warning about lifestyle and training

Fortune is deeply conservative (in the small-c sense) when it comes to psychic hygiene. She warns repeatedly against:

- Drugs, alcohol, and overstrain – anything that weakens the nervous system or blurs the boundaries of consciousness is, in her view, an open door to trouble.

- Drifting into magical experimentation without a formal training system – she devotes a whole chapter to “The Risks Incidental to Ceremonial Magic,” arguing that unsupervised dabbling in rituals, trance states, or mediumship can destabilize people who don’t have the structure to integrate what they’re doing. (I personally can attest to this danger.)

In other words: don’t blow holes in the hull and then complain if water comes in.

How Fortune classifies psychic attack

One of the most useful parts of the book is her taxonomy of attacks.

1. Conscious, intentional occult attack

This is the thing everyone worries about: an occultist or magician, working within a deliberate ritual system, who decides to target someone through curses, dream invasion, vampirism, or other methods. Fortune describes this as real, but rare. The logistics are demanding, and not many people have both the skill and the motivation.

She gives concrete examples from her own life, such as the employer who apparently used hypnotic pressure and suggestion to break down her staff—an incident she analyses in terms of “mind-power” abuse and extrusion of the etheric body.

2. Non-human or discarnate entities

Here she ranges from “vampiric” relationships (where one person is, consciously or not, feeding on another’s vitality) to hauntings, elemental forces, and what she calls “the pathology of non-human contacts.”

In Fortune’s view, we live in a crowded psychic ecosystem. Most of the time, boundaries hold. Occasionally, they don’t.

When we notice Them, They notice back.

She takes seriously the possibility of demonic or earthbound-spirit interference: again, as rare but not impossible extremes. When those cases are diagnosed, the remedy looks a lot like what we’d now call deliverance or exorcism, often backed by structured ritual and a supporting community.

3. Unintentional “natural magic” from other people

This is perhaps the most psychologically interesting category. Fortune argues that some people carry a kind of natural psychic charge. They may have no occult training and no conscious intent to harm, but their emotional fixations, jealousy, obsession, or fear act as a steady, erosive pressure on those around them.

In modern language, we might talk about “toxic dynamics” or “narcissistic supply.” Fortune would agree with those descriptions—and then suggest there is also an energetic dimension, a real vampiric drain, that goes beyond metaphor.

In practice, this may be the kind of attack most readers recognize: the person whose presence leaves you exhausted, whose crises colonize your imagination, whose fixation sits in the back of your mind long after they’ve left the room. A classic psychic vampire.

Differential diagnosis: when the mystic meets the lunatic

One of the more striking lines in the preface is Fortune’s comment that the mystic and the lunatic share “the strange by-ways of the mind.” She’s not being glib. She knows that visionary states, dissociation, trauma responses, and genuine spiritual experiences all draw on the same mental hardware, and that a misfire in one place can look very similar to illumination in another.

So in the middle of the book she walks through what we might now call:

- Red flags for purely subjective disturbance: Where the pattern of symptoms, personal history, and response to suggestion all point toward psychological rather than occult causes.

- Indicators that something else may be in play: Recurring patterns across witnesses, physical anomalies in a place, or experiences that behave as though they have an independent center of gravity, not just the person’s expectations.

Crucially, she doesn’t argue that mental illness excludes spiritual interference. In some cases she suggests that psychic vulnerability and psychological fragility travel together: an already-strained mind may be easier to disturb, whether by human predators or by non-human forces.

This is where the book feels oddly contemporary. We’re used to talking about trauma, attachment wounds, and neurodivergence. Fortune is using a different vocabulary, but she’s trying to answer similar questions: how do you help someone who is suffering without collapsing everything into a single explanation?

Methods of defense: from ordinary life to ritual extremes

Readers coming for techniques will find them mostly in Part IV, where she talks about:

- Strengthening the physical and emotional baseline: Adequate rest, good food, sane routines, satisfying work, and relationships that aren’t parasitic. It’s not glamorous, but for Fortune, psychic defense begins with a reasonably ordered life.

- Magical and religious protections: Ritual banishings, prayers, sacraments, consecrated objects, and what we might call boundary-setting in the astral body.

- Community and lineage: Working within an established tradition, under guidance, as a safeguard against both self-delusion and predatory teachers. She’s adamant that solitary dabbling in ceremonial magic multiplies risk.

- Exorcism and major interventions – reserved for extreme cases, where the practitioner judges that there is a genuine hostile presence that won’t respond to lesser measures. At that point, she treats the situation as a serious operation rather than a casual house-clearing.

The through-line is simple: awareness first, then diagnosis, then action proportional to what’s actually happening.

Why read Psychic Self-Defense now?

Fortune wrote as someone who had walked through breakdown, rebuilt her life around structured spiritual practice, and then spent years trying to keep other people from falling into the same traps. Whether you share her metaphysics or not, Psychic Self-Defense is a fascinating artifact from the period when modern psychology and modern occultism were still working out their uneasy relationship.

If nothing else, it’s a useful reminder: awareness is itself a kind of protection. Naming the pattern—whether we call it psychic vampirism, emotional abuse, or a bad magical experiment—gives us room to respond, rather than simply endure.

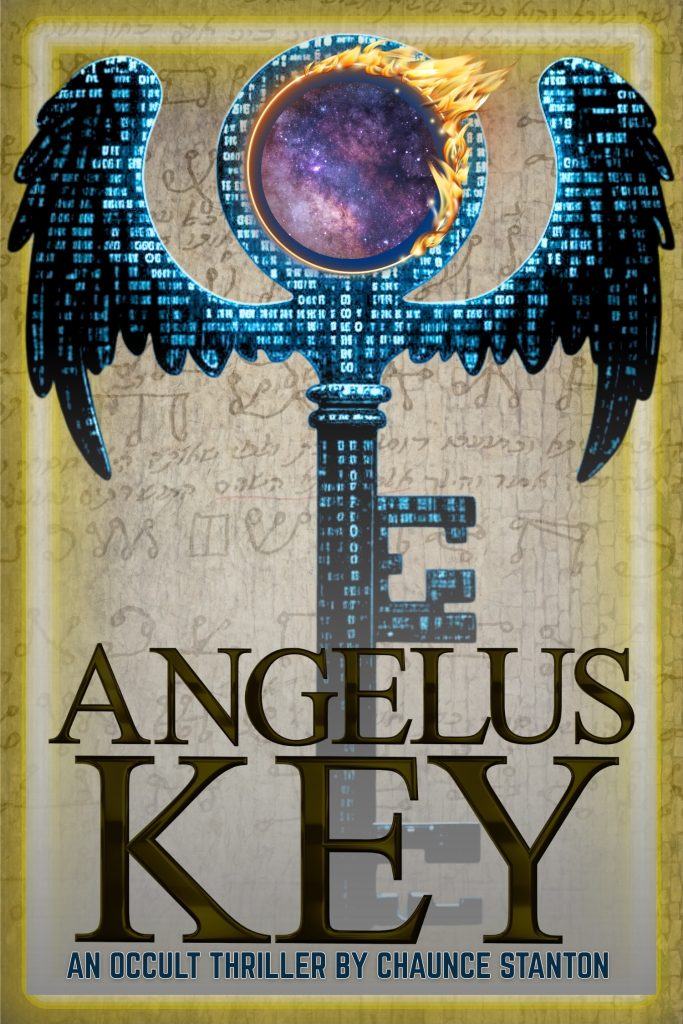

For me, that tension between psychology and the paranormal is exactly where my occult thriller, The Angelus Key, lives. Dion Fortune asks how we tell the difference between an injured mind and an injured soul, and my protagonist, Dr. Stephen Dunlop, spends most of the novel caught in that same borderland: sorting data from delusion, nervous collapse from genuine contact with something other, all within a magickal reality.

The Angelus Key takes Fortune’s world of occult orders, psychic attack, and unseen influence and drops it into a contemporary setting shaped by surveillance tech, algorithms, and weaponized belief. If Psychic Self-Defense gives you a taste for the questions (What if some attacks aren’t just in our heads? What if the “defenses” we build can be turned against us?) then The Angelus Key is my attempt to explore those possibilities in story form, with all the ambiguity, dread, and hard choices that entails.